From Aisha to Fatima al-Fihri: Deconstructing Masculine Narratives in Classical Islamic Historiography

Main Article Content

Abstract

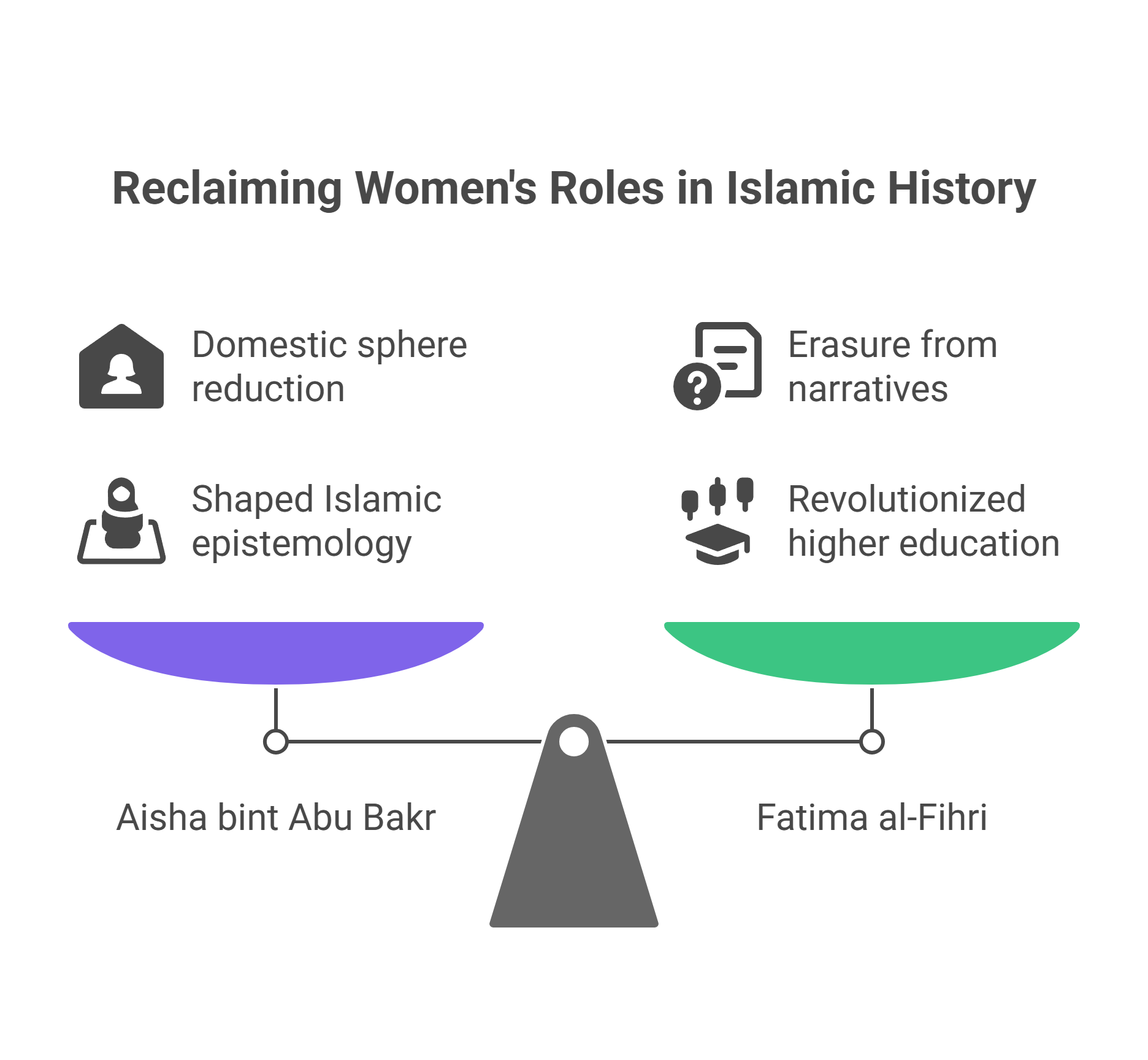

Classical Islamic historiography has long been dominated by masculine narratives that marginalize women from central roles in history. This study deconstructs such bias by examining t he representation of Aisha bint Abu Bakr and Fatima al-Fihri in texts such as Tarikh al-Tabari and al-Kamil fi al-Tarikh. The analysis reveals that Aisha, an authority on hadith and jurisprudence, is reduced to the domestic sphere, while Fatima al-Fihri, the founder of Al-Qarawiyyin University, is erased from narratives despite her monumental contributions. Through reinterpretation, both are positioned as transformative agents: Aisha shaped early Islamic epistemology, and Fatima revolutionized higher education. This study proposes a reconstruction of inclusive narratives that challenge patriarchal hegemony, offering academic and social implications—from enriching historical understanding to supporting gender equality in modern Islam. The findings affirm that masculine bias is not incidental but an ideological construct that impoverishes the understanding of Islamic civilization. By situating women as historical subjects, this study not only corrects past distortions but also paves the way for a more equitable and holistic Islamic discourse.

Downloads

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

References

G. Darzi, A. Ahmadvand, and M. Nushi, “Revealing gender discourses in the qur’ān: An integrative, dynamic and complex approach,” HTS Teol. Stud. / Theol. Stud., vol. 77, no. 4, pp. 1–11, 2021, doi: 10.4102/hts.v77i4.6228.

L. Ouzgane, Islamic masculinities. 2008. [Online]. Available: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85187610233&partnerID=40&md5=13f8ec96edbfb07efe3a53fa929a759b

A. Sayeed, Women and the transmission of religious knowledge in Islam. 2010. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139381871.

Ö. Sabuncu, “The life of ’A’isha bt. Abi Bakr, personality and her place in Islamic history,” Cumhur. Ilah. Derg., vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 2103–2105, 2017, [Online]. Available: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85045752471&partnerID=40&md5=0d3a8362b30c06fd20b0d3859e9903cd

G. Hardaker and A. A. Sabki, “An insight into Islamic pedagogy at the University of al-Qarawiyyin,” Multicult. Educ. Technol. J., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 106–110, 2012, doi: 10.1108/17504971211236308.

F. F. Cengic, “Fatima Al Fihri Founder of the First World University,” Stud. Media Commun., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 14–20, 2020, doi: 10.11114/smc.v8i2.4903.

P. Miller, Patriarchy. 2017. doi: 10.4324/9781315532370.

G. Gangoli, “Understanding patriarchy, past and present: Critical reflections on gerda lerner (1987), the creation of patriarchy, oxford university press,” J. Gender-Based Violence, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 127–134, 2017, doi: 10.1332/239868017X14907152523430.

J. W. Scott, Sex and Secularism. 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85199492691&partnerID=40&md5=19cdced84a934a80e3e21925eddb44ea

H. M. Stur, “Gender and sexuality,” in The Routledge History of Global War and Society, 2018, pp. 285–295. doi: 10.4324/9781315725192.

P. Zazueta and E. Stockland, Gender and the politics of history. 2017. doi: 10.4324/9781912281633.

J. M. Salem, “Women in Islam: Changing interpretations,” Int. J. Humanit., vol. 9, no. 12, pp. 77–91, 2013, [Online]. Available: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84876536087&partnerID=40&md5=a9790d3d1e93774f9066198b81633aae

L. Ahmed and K. Ali, Women and gender in islam: Historical roots of a modern debate. 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85103684548&partnerID=40&md5=edb18e31a7693bc690b2d899db100508

C. B. S. Strobel, “Different Foundations for Islamic Feminisms: Comparing Genealogical and Textual Approaches in Ahmed and Parvez,” in Globalizing Political Theory, 2022, pp. 60–68. doi: 10.4324/9781003221708-9.

A. Moghadam and T. Lovat, Power-Knowledge in Tabari’s «Histoire» of Islam: Politicizing the past in Medieval Islamic Historiography. 2019. doi: 10.3726/b15567.

A. Moghadam and T. Lovat, “On the Significance of Histoire: Employing Modern Narrative Theory in Analysis of Tabari’s Historiography of Islam’s Foundations,” in Education, Religion, and Ethics - a Scholarly Collection, 2023, pp. 173–183. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-24719-4_12.

S. Syamsiyatun, “Redefining Manhood and Womanhood: Insights from the Oldest Indonesian Muslim Women Organization, ’Aisyiyah,” Stud. Islam., vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 547–573, 2023, doi: 10.36712/sdi.v29i3.23455.

M. Mehfooz, “Women and hadith transmission: Prolific role of Aisha in validation and impugnment of prophetic traditions,” AlBayan, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 200–227, 2021, doi: 10.1163/22321969-12340099.

F. Harpci, “’Ā’isha, mother of the faithful: The prototype of Muslim women Ulama,” Al-Jami’ah, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 159–179, 2015, doi: 10.14421/ajis.2015.531.159-179.

S. Rehman, Gendering the hadith tradition: Recentring the authority of Aisha, mother of the believers. 2024. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780192865984.001.0001.

S. Ahmed, “Learned women: three generations of female Islamic scholarship in Morocco,” J. North African Stud., vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 470–484, 2016, doi: 10.1080/13629387.2016.1158110.

R. Barlow and S. Akbarzadeh, “Women’s rights in the muslim world: Reform or reconstruction?,” Third World Q., vol. 27, no. 8, pp. 1481–1494, 2006, doi: 10.1080/01436590601027321.

K. Karoui, “Rereading of the classical Islamic heritage for a contemporary grammar of justice: The works of Fatima Mernissi and Mohammed Arkoun,” Dtsch. Z. Philos., vol. 68, no. 6, pp. 914–927, 2020, doi: 10.1515/dzph-2020-0062.

A. Bakar, “Women on the Text According to Amina Wadud Muhsin in Qur’an and Women,” Al-Ihkam J. Huk. dan Pranata Sos., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 167–186, 2018, doi: 10.19105/al-lhkam.v13i1.1467.

F. Zenrif and S. Bachri, “Critical Study of Amina Wadud’s Thought in the Issue of Inheritance,” Jure J. Huk. dan Syar’iah, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 39–53, 2023, doi: 10.18860/j-fsh.v15i1.22217.

D. D. Zimmerman, “Young Muslim women in the United States: identities at the intersection of group membership and multiple individualities,” Soc. Identities, vol. 20, no. 4–5, pp. 299–313, 2014, doi: 10.1080/13504630.2014.997202.

M. A. Ismail, “A comparative study of Islamic feminist and traditional Shi’i approaches to Qur’anic exegesis,” J. Shi’a Islam. Stud., vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 166–195, 2016, doi: 10.1353/isl.2016.0014.

F. Ahmadi, “Islamic feminism in Iran: Feminism in a new Islamic context,” J. Fem. Stud. Relig., vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 33–53, 2006, doi: 10.2979/FSR.2006.22.2.33.

M. Bakhshizadeh, “A Social Psychological Critique on Islamic Feminism,” Religions, vol. 14, no. 2, 2023, doi: 10.3390/rel14020202.

K. Bauer, Gender hierarchy in the Qur’ān: Medieval interpretations, modern responses. 2015. doi: 10.1017/9781139649759.

J. Akhtar, “Social Justice and Equality in the Qur’ān: Implications for Global Peace,” Unity and Dialogue, vol. 79, no. 1, pp. 23–45, 2024, doi: 10.34291/Edinost/79/01/Akhtar.

D. Rizal and D. Putri, “Reinterpreting Religious Texts on Gender Equality: The Perspective of Ahmad Syafii Maarif,” Juris J. Ilm. Syariah, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 327–336, 2024, doi: 10.31958/juris.v23i2.10233.

T. Štojs, “Some aspects of the position of women in Islam,” Obnovljeni Ziv., vol. 67, no. 2, pp. 179–194, 2012, [Online]. Available: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84873111735&partnerID=40&md5=54872179ba9955f7b9b45babb9b200cf

F. Shahin, “Islamic Feminism and Hegemonic Discourses on Faith and Gender in Islam,” Int. J. Islam Asia, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 27–48, 2020, doi: 10.1163/25899996-01010003.

M. J. Carrera-Fernández, J. Guàrdia-Olmos, and M. Peró-Cebollero, “Qualitative research in psychology: Misunderstandings about textual analysis,” Qual. Quant., vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 1589–1603, 2013, doi: 10.1007/s11135-011-9611-1.

J. Kates, Deconstruction: “History, if there is history.” 2021. doi: 10.4324/9780367821814-23.

M. Mason, “Historiospectography? Sande Cohen on Derrida’s Specters of Marx,” Rethink. Hist., vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 483–514, 2008, doi: 10.1080/13642520802439723.

J. O. Shanahan, Literature Reviews. 2024. doi: 10.4324/9781003436287-2.

M. Hayford and J. O. Shanahan, Literature reviews. 2021.

B. Boloix-Gallardo, “Beyond the Haram: Ibn al-Khatib and his privileged knowledge of Royal Nasrid women,” Mediev. Encount., vol. 20, no. 4–5, pp. 383–402, 2014, doi: 10.1163/15700674-12342180.

O. Israfi, “Penafsiran Ibnu Jarir Al-Thabari dan Muhammad Quraish Shihab terhadap Lafadz al-Ṭhayibât dan al-Khâbisâth dalam Surat al-Nur Ayat 26,” Universitas Islam Negeri Ar-Raniry, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://repository.ar-raniry.ac.id/id/eprint/36616/

I. A. Idris, Klarifikasi Al-Quran Atas Berita Hoaks. Jakarta: PT Alex Media Komputindo, 2018.

I. Itrayuni, A. Ashadi, and F. Faizin, “Kontekstualisasi Surah al-Nūr Ayat 11-20 Pada Open Journal System Indonesia Kontemporer,” Mashdar J. Stud. Al-Qur’an dan Hadis, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 19–34, 2022, doi: 10.15548/mashdar.v4i1.4619.

L. Rahbari, “‘mother of her father’: Fatima-zahra’s maternal legacy in shi’a islam,” J. Shi’a Islam. Stud., vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 23–41, 2018, doi: 10.1353/isl.2018.0004.

Z. S. Kaynamazoǧlu, “Ayyam-e Fatimiyya as an Alternative ‘Ashura’: The Mourning of Fatima in Modern Iran | Alternatif Bir ’Âşûrâ Olarak Eyyâm-i Fâtimiyye: Modern Iran’da Hz. Fâtima’nin Matemi,” Islam Tetkikleri Derg., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 229–248, 2024, doi: 10.26650/iuitd.2024.1398696.

A. Simon, The florentine union and the late medieval Habsburgs in Transylvania on the eve of the first world war: On the institutional and scholarly impact of Augustin Bunea. 2023.

R. Roded, “Human Creation in the Hebrew Bible and the Qur’an – Feminist Exegesis,” Relig. Compass, vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 277–286, 2012, doi: 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2012.00352.x.

I. Ahmad, Cracks in the ‘mightiest fortress’: Jamaat-e-Islami’s changing discourse on women. 2011. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139382786.013.

A. King, “Islam, women and violence,” Fem. Theol., vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 292–328, 2009, doi: 10.1177/0966735009102361.

M. Yüksel, “Some Findings Regarding the Chain of Narrators (Sanad) and Textual Content (Matn) Evaluation of the Reports About the Barking of Hawaab Dogs,” Cumhur. Ilah. Derg., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 5–21, 2021, doi: 10.18505/cuid.851782.

H. Gürkan and A. Serttaş, “Beauty Standard Perception of Women: A Reception Study Based on Foucault’s Truth Relations and Truth Games,” Inf. Media, vol. 96, pp. 21–39, 2023, doi: 10.15388/IM.2023.96.64.

A. C. P. Junqueira, T. L. Tylka, S. D. S. Almeida, T. M. B. Costa, and M. F. Laus, “Translation and Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Broad Conceptualization of Beauty Scale With Brazilian Women,” Psychol. Women Q., vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 351–371, 2021, doi: 10.1177/03616843211013459.

H. French and M. Rothery, “Hegemonic Masculinities? Assessing Change and Processes of Change in Elite Masculinity, 1700–1900,” in Genders and Sexualities in History, 2011, pp. 139–166. doi: 10.1057/9780230307254_8.

C. T. Benchekroun, “The Idrisids: History against its history,” Al-Masaq J. Mediev. Mediterr., vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 171–188, 2011, doi: 10.1080/09503110.2011.617063.

L. Skogstrand, Warriors and other men: Notions of masculinity from the late bronze age to the early iron age in scandinavia. 2016. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1pzk27z.

I. Erwani and A. S. Siregar, “The Role of Women in Islamic Sacred Texts: A Critical Study of Women’s Narratives and Authority in Islamic Tradition,” Pharos J. Theol., vol. 106, no. 1, pp. 1–14, 2025, doi: 10.46222/PHAROSJOT.106.6.

Í. Almela, “MONUMENTAL ARCHITECTURE FOR HYGIENE AND PURIFICATION: TWO ABLUTION HALLS FROM THE ALMOHAD PERIOD IN FEZ (MOROCCO),” Anu. Estud. Mediev., vol. 54, no. 2, 2024, doi: 10.3989/aem.2024.54.2.1392.

F. Griffel, Al-Ghazali’s Philosophical Theology. 2009. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195331622.001.0001.

J. Erasmus, “Al-Ghazālī’s Kalām Cosmological Argument,” in Sophia Studies in Cross-cultural Philosophy of Traditions and Cultures, vol. 25, 2018, pp. 53–64. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-73438-5_4.